Hydrogen Sulfide Update 2026: The Hidden Link Between Your Microbiome and Health

Hydrogen Sulfide Update 2026: The Hidden Link Between Your Microbiome and Health You may have heard that your gut microbiome influences ...

0 item(s)

Free delivery on tests

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the most challenging chronic conditions faced by patients and clinicians alike. Classified as a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), UC affects the lining of the colon and rectum, leading to persistent inflammation, ulcers, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and bleeding. While treatments have advanced considerably, the exact cause of ulcerative colitis remains elusive. Instead, modern research points to a web of interrelated factors: genetics, the immune system, the gut microbiome, and environmental triggers. In this article, I’ll guide you through the scientific evidence on what causes ulcerative colitis, drawing from clinical research, genetics, microbiology, and immunology.

Unlike conditions caused by a single gene mutation or infection, UC is what researchers call a multifactorial disease. This means multiple influences—none of which alone can explain the disease—come together to set off inflammation.

The consensus today is that ulcerative colitis develops when:

A genetically susceptible individual.

Encounters environmental risk factors.

That disrupt the gut microbiome.

Leading to abnormal immune responses that damage the intestinal lining (or a damaged intestinal lining that leads to abnormal immune responses!).

This “four-hit hypothesis” is supported across decades of research.

Family studies show that first-degree relatives of UC patients have up to a 10-fold increased risk of developing the disease. However, unlike Crohn’s disease, where strong genetic markers such as NOD2 mutations exist, UC genetics appear more complex and diffuse.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified over 200 loci associated with IBD risk, many of which overlap between UC and Crohn’s disease. UC-specific associations include variations in genes regulating:

Immune response pathways (e.g., IL23R, HLA variants).

Gut barrier integrity (e.g., ECM1, MUC genes involved in mucin production).

Autophagy and cell stress responses.

Genetics set the stage, but by themselves, they rarely cause disease. In fact, twin studies reveal only about a 15–20% concordance rate in identical twins with UC. This underscores the role of other triggers.

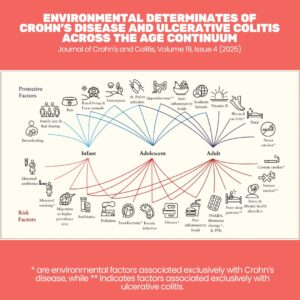

Why do some people with genetic risk never develop UC, while others do? Environmental triggers are the missing piece.

Some of the most studied risk factors include:

Diet: High intake of processed foods, low fiber, and high sulfates may alter gut bacteria and increase inflammation.

Infections & antibiotics: Disruption of gut flora during childhood has been linked to later UC onset.

Smoking: Interestingly, smoking seems protective against UC, though harmful for Crohn’s disease.

Stress: While not a direct cause, stress exacerbates flares via immune-neuroendocrine pathways.

Geography: UC is more common in industrialised nations, pointing toward environmental and dietary patterns as contributors.

Our intestines host trillions of microbes—bacteria, viruses, fungi—that normally help with digestion and immune regulation. In UC, this peaceful coexistence breaks down.

Studies show that patients with UC have:

Reduced microbial diversity – fewer beneficial species like Firmicutes.

Increased pro-inflammatory bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Enterobacteriaceae.

Altered metabolites – for example, lower levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which normally strengthen the gut barrier.

Interestingly, probiotic studies have demonstrated that introducing non-pathogenic E. coli strains (like E. coli Nissle 1917) can maintain remission as effectively as the drug mesalazine. This suggests that restoring microbial balance may be as important as suppressing inflammation.

The microbiome may also influence how the immune system misfires in UC. Abnormal immune recognition of commensal bacteria seems to amplify inflammation, turning normally harmless microbes into perceived threats.

UC is considered an immune-mediated disease. Unlike Crohn’s disease (which shows a Th1/Th17 skewed response), UC has features of an atypical Th2 response. This means immune cells produce excessive pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-5 and IL-13, which can damage cells that line the gut.

Key immune abnormalities in UC include:

Epithelial barrier dysfunction (leaky gut) – immune cells attack the lining of the colon, increasing permeability.

Overactive neutrophils – producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage tissue.

Cytokine storms – signalling molecules like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 drive chronic inflammation.

Recent models even suggest that oxidative stress—particularly hydrogen peroxide accumulation in colonic epithelial cells—may be a central driver.

Chronic inflammation in UC doesn’t just cause symptoms—it also sets the stage for long-term risks such as colon cancer. Persistent cycles of epithelial damage, immune activation, and repair can lead to DNA mutations and genomic instability.

This underscores why controlling inflammation is not just about symptom relief, but also about preventing downstream consequences.

Despite decades of research, the cause of UC is still debated. Some emerging hypotheses include:

Redox imbalance: Hydrogen peroxide accumulation as a “first hit”.

Barrier-first models: Damage to the mucus layer and epithelial cells precedes immune activation.

Microbiome-immune feedback loops: Dysbiosis and immune dysfunction reinforce each other in a vicious cycle.

The most honest answer is: ulcerative colitis does not have one single cause. Instead, it is the product of an unfortunate convergence of:

Inherited susceptibility.

Altered gut microbes.

Immune dysregulation.

Environmental triggers.

This “perfect storm” results in a colon unable to maintain harmony between the body’s immune defences and the trillions of microbes that live within it.

For patients, understanding these causes provides reassurance: UC is not your fault. It’s not caused by stress alone, or by eating the wrong foods one day. Instead, what causes ulcerative colitis is a complex disease with roots in biology and environment.

For clinicians and researchers, the multifactorial nature of UC means that therapies need to be equally multifaceted—targeting inflammation, repairing the barrier, and modulating the microbiome.

This is why nutritional therapy and Functional Medicine can be so powerful – it provides practitioners with the understanding and tools to work with multifaceted conditions.

Ulcerative colitis is not caused by a single factor but by a network of genetics, microbes, immunity, and environment. Over the past 30 years, science has shifted from searching for a single “culprit” to understanding UC as a disease of imbalance. This nuanced view explains why some therapies—like probiotics, dietary interventions, and immune-suppressing drugs—work better when combined than alone.

The road to a cure will likely involve precision medicine: tailoring treatment based on an individual’s genetic risk, microbiome composition, and immune profile. Until then, knowledge remains power—for patients managing their condition, and for clinicians guiding care.

Ungaro et al., (2017) Ulcerative colitis, Lancet, 29;389(10080):1756-1770 (click here)

Keshteli et al., (2019) Diet in the Pathogenesis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis; A Review of Randomized Controlled Dietary Interventions, Nutrients, 30;11(7):1498 (click here)

Singh et al., (2022) Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease, United European Gastroenterol J;10(10):1047-1053 (click here)

de Silva et al., (2014) Epidemiology, demographic characteristics and prognostic predictors of ulcerative colitis, World J Gastroenterol, 28;20(28):9458-67 (click here)

Piovani et al., (2019) Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses, Gastroenterology;157(3):647-659.e4. (click here)

Jarmakiewicz-Czaja et al., (2022) Genetic and Epigenetic Etiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Update, Genes (Basel) 16;13(12):2388 (click here)

Rembacken, B.J., et al. (1999). Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli versus mesalazine for treatment of UC. The Lancet, 354(9179), 635–639. (click here)

Chhippa et al., (2025) Environmental risk factors of inflammatory bowel disease: toward a strategy of preventative health (click here)