Hydrogen Sulfide Update 2026: The Hidden Link Between Your Microbiome and Health

Hydrogen Sulfide Update 2026: The Hidden Link Between Your Microbiome and Health You may have heard that your gut microbiome influences ...

0 item(s)

Free delivery on tests

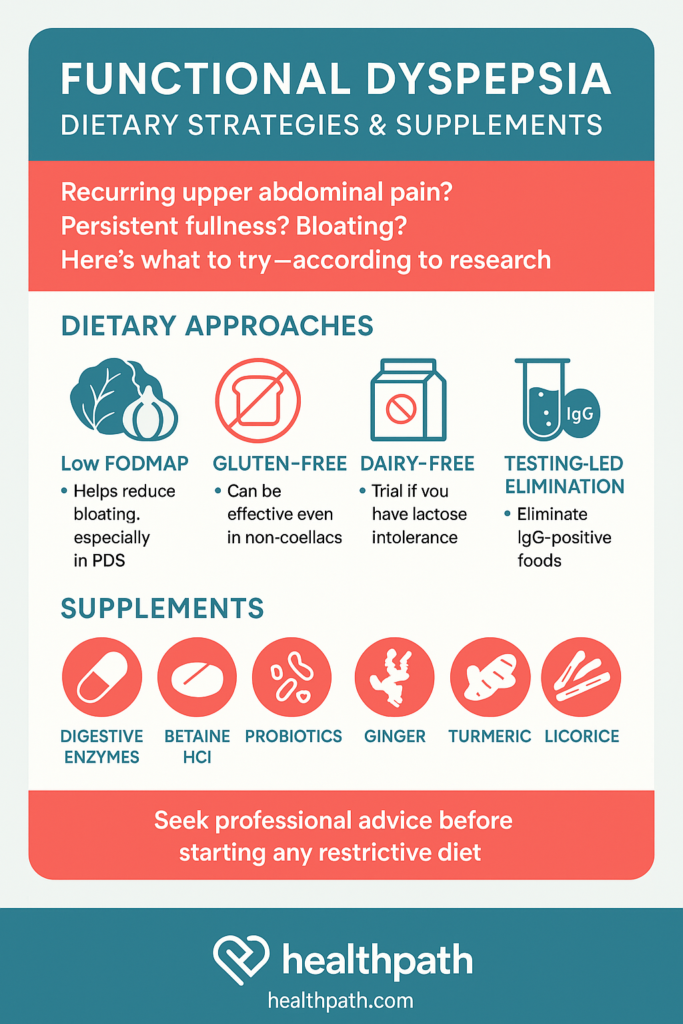

Have you ever felt bloated, full, or had upper abdominal pain after eating—yet your medical tests came back normal? You’re not alone. These symptoms may be due to functional dyspepsia (FD)—a common yet often misunderstood digestive disorder that affects about 1 in 5 people globally (Talley et al., 2015).

In this blog, we unpack the latest insights into functional dyspepsia and explore dietary strategies and supplements that may help bring relief.

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a common but often misunderstood digestive disorder that affects the upper part of the stomach. Unlike conditions caused by visible damage or disease—such as ulcers or reflux—functional dyspepsia is diagnosed when a person experiences ongoing digestive discomfort without any identifiable structural or biochemical cause during standard medical testing. People with FD typically report symptoms like upper abdominal pain or burning, early fullness during meals (even after eating a small amount), bloating, and a prolonged feeling of heaviness after eating. These symptoms can significantly affect quality of life, often leading to changes in eating habits, stress, and reduced social or work activity.

What makes FD particularly challenging is that it’s not caused by a single issue. It’s a complex condition with multiple possible triggers. Research suggests that a combination of factors contribute to FD, including subtle inflammation in the gut lining, increased sensitivity to stomach stretching (known as visceral hypersensitivity), delayed stomach emptying, and even disruptions in the way the brain and gut communicate (the gut-brain axis). In some people, a past gastrointestinal infection or ongoing imbalance in the gut microbiome may be involved. For example, SIBO (small intestine bacterial overgrowth) has been connected with functional dyspepsia (Tziatzios e al., 2021). Psychological factors such as stress and anxiety can also play a role in amplifying symptoms, although FD is very much a physical condition—not “just in your head.”

Because there’s no single test or visible cause, diagnosis and treatment often rely on symptom patterns and excluding other possibilities. While medication can help some people, many benefit most from a tailored approach that includes dietary changes, stress management, and sometimes natural supplements. The key is personalisation: what works for one person may not work for another. Understanding the condition, listening to your body, and working closely with a knowledgeable healthcare provider are essential steps toward finding relief.

Current research suggests several contributors:

Immune system activation via eosinophils and Th2 inflammation (Stanghellini et al., 2015).

Microbiome imbalances (Surdea-Blaga et al., 2017).

Gut-brain axis dysfunction (Ford et al., 2017).

Environmental exposures like allergens (Pryor et al., 2020)

The United European Gastroenterology (UEG) and European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM) agree that several mechanisms cause functional dyspepsia. These include impaired gastric accommodation, delayed gastric emptying, hypersensitivity to stomach stretching, Helicobacter pylori infection, and changes in how the brain processes gut signals’. (Wauters et al, 2021)

It’s more common in women, smokers, Helicobacter pylori-positive individuals, and NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) users (Talley et al., 2015, Wauters et al, 2021).

FD is notoriously difficult to treat with standard medications:

H. pylori treatment offers only a small benefit (Moayyedi et al., 2006).

PPIs improve symptoms slightly over placebo (Ford et al., 2017).

Tricyclic antidepressants and prokinetics are sometimes used but lack strong evidence (Cash et al., 2018).

This is not be surprising when we appreciate that everyone has their own unique contributory factors to functional dyspepsia. PPI’s are not going to help someone with SIBO or allergies/intolerances for example.

Conventional dietary advice for functional dyspepsia usually includes eating smaller, more frequent meals and avoiding common trigger foods such as spicy, fatty, or highly processed items, as well as carbonated drinks, caffeine, and alcohol. While this approach can offer some relief, research shows it may not be effective for everyone. Largely because functional dyspepsia isn’t the same in every person. The condition is influenced by a complex mix of gut sensitivity, immune response, microbiome imbalances, and even the brain-gut connection. As a result, generic advice often falls short. A more person-centred approach—one that considers individual food sensitivities, lifestyle, and symptom patterns—is often key to managing FD effectively and sustainably.

Let’s look at some of the evidence for different dietary approaches.

Originally developed for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), the low FODMAP diet reduces fermentable carbohydrates that can cause bloating, gas, and discomfort. Given the overlap between IBS and FD—particularly in those with postprandial distress—this diet has shown promising results in relieving symptoms. Several clinical trials have found that patients with FD who follow a low FODMAP diet report fewer symptoms of fullness and bloating, especially when other approaches haven’t worked (Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2023). While not a first-line therapy for everyone, it can be a valuable tool in cases where traditional dietary guidance falls short—particularly when implemented under the guidance of an experienced nutritional therapist to avoid unnecessary restriction.

Many people associate gluten with coeliac disease, but it can also trigger digestive symptoms in those without a formal diagnosis. In functional dyspepsia—particularly when symptoms like bloating and early fullness occur—a gluten-free diet can provide relief, even if testing has ruled out coeliac disease. One study found that about 35% of individuals with refractory FD improved after following a gluten-free diet. When they reintroduced gluten in a blinded challenge, some experienced a return of symptoms (Sci Rep, 2020). A meta-analysis also confirmed that gluten exposure worsens symptoms like epigastric pain and early satiety (Zhao et al., 2023). Because responses vary, it makes sense to trial gluten removal under guidance and reintroduce it carefully to determine whether it acts as a trigger.

For some people with functional dyspepsia, dairy products can be problematic—either due to lactose intolerance or sensitivity to milk proteins. These can cause or worsen symptoms such as bloating, discomfort, and nausea. One study found that eliminating dairy for just one month resulted in a significantly greater reduction in symptoms compared to those on an unrestricted diet (Arab J Gastroenterol, 2024). Additionally, non-IgE-mediated milk protein allergy has been linked to functional digestive symptoms in sensitive individuals. This makes a dairy-free trial a reasonable and low-risk option when tailored to the person’s dietary history and symptom pattern.

The Mediterranean diet, rich in vegetables, fruits, olive oil, whole grains, legumes, and moderate amounts of fish and dairy, hasn’t been studied as extensively in functional dyspepsia as other conditions. However, its anti-inflammatory and gut-friendly properties make it a promising long-term approach. Unlike restrictive diets, the Mediterranean pattern encourages nutrient diversity, supports a healthy gut microbiome, and may reduce low-grade inflammation—one of the suspected contributors to FD. While direct research on its effects in FD is still emerging, observational data suggest that lower intake of ultra-processed foods (which the Mediterranean diet naturally avoids) is associated with fewer dyspeptic symptoms (Front Psychiatry, 2020). For individuals seeking a sustainable, whole-food approach, this diet offers both symptom support and broader health benefits.

People with functional dyspepsia who suspect food sensitivities often explore IgG or IgE-based food antibody testing to guide personalised elimination diets. These tests attempt to detect immune responses to specific foods that might trigger symptoms like bloating, discomfort, or nausea. Although current evidence for IgG-guided elimination remains limited, one study showed that some individuals with FD or overlapping IBS experienced symptom relief after removing foods identified by the tests. When they reintroduced those foods, their symptoms returned (Acta Gastroenterol Belg, 2018). However, these tests do not diagnose food intolerance or allergy and require careful interpretation. Because food-related symptoms in FD vary widely, individuals should follow elimination diets under the guidance of a healthcare professional to avoid unnecessary restriction. When used thoughtfully, testing can support dietary exploration in persistent or complex cases.

Cutting out certain foods doesn’t help everyone the same way. That’s why it’s important for healthcare professionals to give personalised advice. There’s no one-size-fits-all diet. The best approach is to listen to your body and avoid foods that clearly cause discomfort. Also aim to eat smaller, more frequent meals while limiting high-fat foods. (Popa et al., 2022)

Digestive enzymes help the body break down food into nutrients, making digestion more efficient. This can be particularly helpful for those with food intolerances or subtle enzyme deficiencies. In functional dyspepsia, they may relieve symptoms such as bloating, fullness, and indigestion after meals. A placebo-controlled clinical trial found that a multi-enzyme formula taken twice daily with meals significantly reduced dyspeptic symptoms. It even improved sleep over two months (Biomed Pharmacother, 2023).

Recommended Product: Digestive Enzymes

Betaine hydrochloride (HCl) is a compound that temporarily increases stomach acid levels. This may be helpful in FD, especially for those experiencing symptoms of low stomach acid. A small study found that 30.8% of people with FD saw over 50% improvement in symptoms after taking Betaine HCl with pepsin for six weeks. (BMC Gastroenterol, 2017) Another study confirmed that 1,500 mg of Betaine HCl can rapidly lower stomach pH, making it functionally effective (Mol Pharm, 2013). However, it’s essential to use this under supervision, especially if a person has a history of reflux or ulcers.

Recommended Product: Betaine HCI

Probiotics are beneficial bacteria that support gut health and modulate the immune system. In FD, they may help restore balance in the stomach and small intestine microbiome, improving symptoms like bloating. One randomised clinical trial found that a specific blend of Bacillus coagulans and Bacillus subtilis significantly improved FD symptoms. Interestingly, benefits were sustained even 16 weeks after treatment (Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021). Probiotics may also enhance treatment outcomes in patients on long-term PPIs or with low-grade inflammation. For best results, strain-specific, evidence-based products should be selected.

Recommended Product: Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG and Saccharomyces boulardii

Ginger is well known for its anti-nausea properties, but it also improves motility—the movement of food through the stomach. This is often impaired in FD. A randomised trial comparing ginger extract to placebo found that 79% of people taking ginger experienced improvement. This including reduced post-meal fullness and bloating (Cureus, 2023). Another study found ginger increased gastric emptying, making it helpful where delayed digestion is part of the picture (World J Gastroenterol, 2011). Doses of 1,000–1,500 mg per day are commonly used in studies.

Recommended Product: Organic Ginger

Curcumin, the active compound in turmeric, has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. In functional dyspepsia, it may help calm low-grade gut inflammation and improve symptoms. In fact, clinical trials have shown that curcumin performs similarly to omeprazole (a PPI) in reducing FD symptoms (BMJ, 2023). Doses typically range from 500–1,000 mg of curcuminoid extract daily, or 2,000 mg turmeric powder. It’s well tolerated and may be ideal for those seeking a natural alternative to acid-suppressing medications.

Recommended Product: Curcumin

Deglycyrrhizinated licorice (DGL) is a form of licorice processed to remove glycyrrhizin, making it safer for long-term use. DGL helps protect and heal the gut lining, and may also suppress H. pylori, a bacterium often implicated in FD. In a clinical trial, DGL significantly improved FD symptoms within 30 days compared to placebo . Another trial showed that it helped reduce H. pylori positivity rates when used alone (Evd Based Comp Alt Med, 2019). Typical doses are around 150 mg/day, taken in divided doses, preferably before meals.

Recommended Product: DGL

| Supplement | Purpose | Clinical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Digestive enzymes | Intolerance, bloating | As recommended by product. |

| Betaine HCl | Postprandial fullness | 650mg to 1500 mg betaine HCI with meals |

| Probiotics* | Microbiome, PPI-related dyspepsia | A trial of a specific strain for specific purposes. |

| Ginger | Nausea, motility, H. pylori | 50mg gingerols per day. |

| Turmeric/Curcumin | Anti-inflammatory | Possible altnernative to omeprazole. 500mg-1000mg daily. |

| Licorice (DGL) | H. pylori, | 150mg daily of DGL |

*Various probiotics have been investigated with functional dyspepsia. Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG and Saccharomyces boulardii (among others) have been found helpful.

Functional dyspepsia is a common and frustrating condition. Medications may only go so far, but personalised nutrition strategies, evidence-backed supplements, and lifestyle changes offer powerful tools for relief.

Always consult your healthcare provider before making major dietary or supplement changes—especially if you have underlying health issues.